The 2030 Agenda and the emerging bioeconomy: making room for policy coherence at the crossroads

The SDG Summit in September this year is an opportunity for streamlining policy coherence in the context of an emerging bioeconomy. On this occasion, I share my views resulting from my participation in three events that shaped my insights into the interconnections of the 2030 Agenda, bioeconomy, and policy coherence.

First of such events was my participation in the UN System Staff College (UNSSC) Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development (PCSD) online course, which allowed me to analyse Ecuador’s PCSD approaches in the context of its bioeconomy policy. Second, the opportunity to join the SD Transition Forum (SDTF) organised by the UN Office for Sustainable Development, which aimed to establish an interface between the High-level Political Forum (HLPF) and the different state and non-state actors and stakeholders involved in implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Lastly, my participation at the Science for Biodiversity Forum at the UN Biodiversity Conference focused on bringing together scientists and policymakers to discuss what scientists could offer to the preparation of the post-2020 biodiversity agenda and fostering socio-ecological transitions pathways.

The importance of policy coherence in the context of sustainable development

Policy coherence is a necessary condition to achieve a politically feasible and cost-effective implementation of the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Policy coherence can be thought of as a means to address systemic issues in policymaking. It provides a framework and tools to build ownership for the 2030 Agenda, to engage stakeholders, to build partnerships, and to analyse appropriate policy mixes based on country contexts. It offers a monitoring framework to track progress at the local, national, regional, and international level while considering transboundary and intergenerational aspects in policymaking (OECD, 2016, 2018a, 2018b).

This year’s HLPF is unique as it will have completed a full cycle of thematic reviews of the 17 goals. It will also convene twice this year: under the auspices of ECOSOC in July and under the auspices of the General Assembly in September in a meeting known as the SDG Summit.

During the SD Transition Forum (SDTF) meeting in 2018, it considered progress on the 2030 Agenda as an integrated whole and the SDGs as a set of interrelated goals and targets aimed at securing a sustainable development transition. In the Incheon Communiqué resulting from the 2018 SDTF, participants noted that 2019 will represent “a crucial moment” in strengthening political will for implementing the 2030 Agenda (UNOSD, 2018). The SDTF recommended various measures to promote SDG implementation including the need for the HLPF to provide strong policy guidance, focus on interlinkages and policy coherence across the 2030 Agenda, and share successes by innovators and “early achievers” of the SDGs.

The case of bioeconomy as a feasible option for paradigmatic shifts towards a sustainable global society

Bioeconomy is defined as the industrial transition to the sustainable use of aquatic and terrestrial biological resources in intermediate and final products for economic, environmental, social and national security benefits (Golden & Handfield, 2014). It incorporates a set of economic activities related to the research, development, production and use of biological products and processes (OECD, 2009).

Bioeconomy is receiving growing attention as an alternative to a global transition to sustainable development. Countries across the globe increasingly confront development decisions that require arrangements to align social and economic dynamics in harmony with nature while addressing poverty challenges. These decisions typically require consideration of biophysical, political, economic, among other factors. Bioeconomy needs to address those challenges in order to become a sustainable economic model (Sillanpää and Ncibi, 2017).

Within this context, sustainable bioeconomy is being rethought in tropical megabiodiverse developing countries. Megabiodiverse countries face increasing pressures for biodiversity conservation during on-going development efforts. While countries like Ecuador had made significant efforts to combat poverty during the last decade, recent research highlights the increasing rate of biodiversity loss and the need for ambitious policy approaches to address it (WWF, 2016).

In response to these and other threats, Ecuador has created an innovative policy arrangement aimed at promoting biodiversity at the centre stage of efforts to achieve long-term economic performance that allow moving away from the middle-income trap and oil-dependence. These policies range from environmental, science and technology, and industrial policies to incentive-based institutions (e.g., fiscal and monetary policy) (Ortega-Pacheco et al. 2018). This view follows previous research arguing that models of development must move away from narrow concern with macroeconomic imbalances and poverty-alleviation safety nets to confront head-on the structural inequalities while addressing sustainability (Rival et al. 2015). It also builds on literature underpinning the critical importance of fostering specific uses for biodiversity as means to ensure its conservation and address rural inequities (Espinel, 2009; Golinelli et al. 2015) and exploring Ecuador socio-ecological transitions (Falconí and Vallejo, 2012).

One option for the bioeconomy to play a critical role in the development of tropical megadiverse countries is to address rural sector challenges in the context of Agenda 2030 implementation. Bioeconomy is argued to have the potential to create growth in the rural economy and create a higher level of self-sufficiency for farm and non-farm rural communities (Golden & Handfield, 2014). One of the main issues arising in the analysis of alternative development models are the trade-offs between the relative participation of the bioeconomy sector in GDP, labour migration, deforestation, biodiversity loss, and industrial and services sectors’ development. Any configuration of bioeconomy should account for complex interdependencies in these variables. The policy coherence for sustainable development (PCSD) framework may serve as a tool to design bioeconomy policy approaches that serve as a vehicle for delivering the sustainable development agenda.

Within this context, Ecuador can offer initial lessons to the world’s sustainable bioeconomy policy approaches. While developed countries’ efforts to transition to bioeconomy involves heavy weightlifting on bioenergy and biomass (see Sillanpää and Ncibi, 2017), Ecuador strategy is centred on the possibility of making biodiversity a key building block of a sustainable economy through its institutional arrangements that promote policy coherence for sustainable development.

The case of Ecuador: sustainable bioeconomy and policy coherence

Ecuador shows that sustainable bioeconomy may provide a coherent approach for the transition to sustainable development. Ecuador provides an interesting case study as it has a track record of mainstreaming the 2030 Agenda in policymaking (see SENPLADES, 2018). Bioeconomy is now a centrepiece of National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP), National Development Plan as well as guides broader economic policy. Without the need to increase governmental apparatuses, Ecuador promoted policy coherence for sustainable development by clarifying and strengthening roles and mandates while incorporating sustainable development as a central guiding principle for policymaking. In order to align existing institutional mechanisms, the 2030 Agenda was adopted as a mandatory orientation for law-making in the National Assembly by a resolution (AN, 2017) and it was declared a state policy by an Executive Decree (Ecuador, 2018). The latter also defines the National Secretariat for Planning and Development (SENPLADES) as the agency responsible to follow up and evaluate SDGs achievement in the country.

The broader institutional arrangement for policymaking established by the Constitution requires SENPLADES to report to the National Planning Council which is a coordinating mechanism in-charge of monitoring progress towards achievement of national targets and reporting on progress. Coordination, monitoring, and evaluation of sectoral and inter-sectoral policy are set by Sectoral Councils. With a view to mainstream equality in public policies, five Equality Councils were established (i.e. Gender, Intergenerational, Peoples and Nationalities, Disabilities and Human Mobility), which consist of representatives of the various functions of the State and civil society. These Councils are part of the National Decentralized Participatory Planning System which formulate agendas for equality. This mechanism integrates equality into planning instruments defined by the different functions of the State and levels of government.

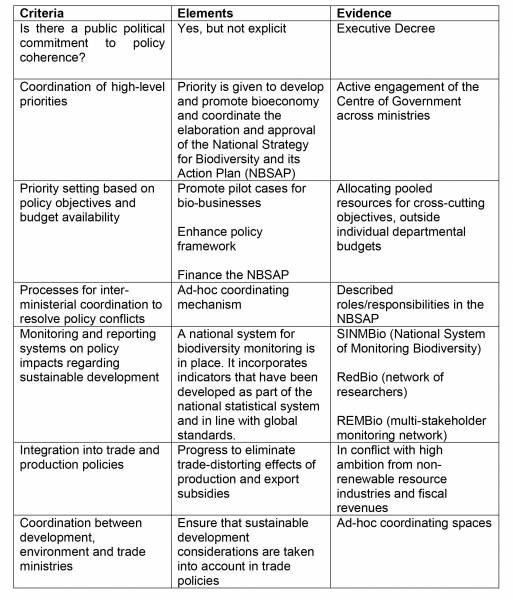

Moreover, a National Group for Strategic Thinking on SDGs has been established with the view to increase vertical and horizontal coordination. It is composed of the National Secretariat for Planning and Development (SENPLADES), the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INEC), the Ministry of Environment, the Ecuadorian Business Committee, universities, the Ecuadorian Confederation of Civil Society Organizations, international organisations such as the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and partners (e.g. delegation of the European Union). See Table 1 below for a summary of institutional factors put in place in Ecuador to foster policy coherence across different levels of government and across different sectors.

Table 1. Policy Coherence for sustainable development institutional factors

Equipped with this PCSD analysis after attending the UNSSC online course on policy coherence for sustainable development, I attended the Science Policy Forum at the UN Biodiversity Conference in Egypt, where I had the opportunity to reflect on various views from scientists around the world in promoting the role of integrated models for policymaking to inform nature-based solutions that can help achieve the SDGs. There was a great appetite to explore priorities for research and policy to advance transitions regarding socio-ecological systems, biodiversity, and benefits from nature. However, there was a clear need to conduct analysis to identify policy coherence issues and improve the understanding of the interactions between biodiversity themes, SDGs and its targets, their implications, and how certain policy actions might support or hinder their achievement.

Despite its inherent importance, the SDG Summit is likely to focus on other priorities beyond the PCSD. However, it is important to keep in mind that a key enabling factor to unleash the potential for new partnerships to deliver on SDGs rely on establishing coherence guidance and incorporating its evidence into Voluntary National Reviews.

Closing

Mainstreaming PCSD in the context of 2030 Agenda and the emerging bioeconomy may offer fruitful grounds for aligning incentives for policymakers to deliver on SDGs. Recent research and observations show that policymakers’ engagement with the SDGs is selective, with an emphasis on those goals and targets which are considered of domestic importance. In fact, evidence from Ecuador suggests that the SDGs cannot be understood as a single coherent template for development that states will simply adopt. Rather they should be analysed in the context of a rapidly changing architecture of global power, shaped by the context-specific nature of national development challenges and national political structures, including decentralization (Horn & Grugel, 2018).

Although there is evidence of the various institutional mechanisms adopted in Ecuador that enhance vertical and horizontal coherence in both executive and legislative branches, SDG monitoring mechanisms were only implemented as part of the elaboration of the Voluntary National Review (VNR). Open public consultations were conducted with stakeholders to assess progress and challenges on SDGs implementation, nevertheless these ad-hoc processes were limited to 5 public consultations that focused on the regional level and only on specific SDGs such as 1, 6, 7, 11, 12, 15 and 17.

The Ecuador VNR highlighted the need to generate appropriate incentives to engage the private sector, academia, and civil society in the achievement of the SDGs and a more effective articulation to formulate policies and other initiatives for the implementation of these objectives at the national level. The Report likewise denoted the presence of political will to carry out shared work that allows implementing the SDGs, but there still remains a lack of access to data, indicators and targets, as well as the limited articulation of national planning instruments with local plans. Strengthening alliances necessitates breaking silos and strengthening collaboration to reduce duplication of efforts and loss of resources.

Given competing economic interests and development inequities, biodiversity may require becoming a strategic and central theme in national economies to ensure the political feasibility of bioeconomic models and PCSD mechanisms. The Ecuadorian experience can provide an example in developing a bio-industry value chain as an institutional arrangement that enables more efficient and integrated use of biological resources towards a sustainable and resilient economy while addressing structural development and biodiversity protection challenges.

Daniel Vicente Ortega Pacheco is Director of the Public Policy Development Center of ESPOL Polytechnic University, Ecuador. He served as Minister of Environment in Ecuador, where he led the creation of the Marine Sanctuary of Galapagos, the new Organic Environmental Code, the National Biodiversity Strategy to 2030, and the National Strategy for Net Zero Deforestation by 2020.

Daniel participated in UNSSC’s online course on Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development in October 2018. UNSSC is accepting applications for the 2019 editions of the course (May and October). Please email sustainable-development@unssc.org.

The opinions, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the United Nations System Staff College, its Board of Governors or its staff.

References:

AN. Legislative Resolution (2017). Retrieved from https://www.asambleanacional.gob.ec/sites/default/files/resolucion_que_compromete_a_la_asamblea_nacional_con_la_implementacion_de _la_agenda_2030_y_los_objetivos_de_desarrollo_sostenible_a_traves_de_todos_sus_actos_legislativos_20-07-2017.pdf

AN. (2018). Informe de avance de actividades ejecutadas por la Asamblea Nacional para el Examen Nacional Voluntario. Quito, Ecuador.

Ecuador. Executive Decree 371 (2018). República del Ecuador.

Golden, J. S., & Handfield, R. (2014). The Emergent Industrial Bioeconomy. Industrial Biotechnology, 10(6), 371–375. https://doi.org/10.1089/ind.2014.1539

Horn, P., & Grugel, J. (2018). The SDGs in middle-income countries: Setting or serving domestic development agendas? Evidence from Ecuador. World Development, 109, 73–84.

OECD (2009) The bioeconomy to 2030: designing a policy agenda. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Paris

OECD. (2016). A new framework for policy coherence for sustainable development. In Better Policies for Sustainable Development 2016. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264256996-6-en

OECD. (2018a). Eight building blocks for coherent implementation of the SDGs. Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development 2018 (pp. 81–109). OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264301061-5-en

OECD. (2018b). Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development 2018. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264301061-en

Ortega-Pacheco, D. V., Silva, A., López, A., Espinel, R., Inclán, D., & Mendoza-Jiménez, M.J. 2018. Towards a sustainable bioeconomy: initial lessons from Ecuador. In Leal Filho, W; Borges de Lima, I.; Pociovalisteanu, D and Paulo Brito (Eds.), Towards a Sustainable Bioeconomy: Principles, Challenges and Perspectives, Switzerland: Springer. 20 p

Rival, L., Muradian, R., & Larrea, C. (2015). New Trends Confronting Old Structures or Old Threats Frustrating New Hopes? ECLAC’s Compacts for Equality. Development and Change, 46(4), 961–978. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12174

SENPLADES. (2018). Examen Nacional Voluntario Ecuador 2018. Quito, Ecuador. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/19627EcuadorVNRReportENVE2018.pdf

Sillanpää, M., & Ncibi, C. (2017). Bioeconomy: Multidimensional Impacts and Challenges. In A Sustainable Bioeconomy (pp. 317–343). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55637-6_9

UNOSD. (2018). 2018 Incheon Communiqué. Summary of the 2018 Sustainable Development Transition Forum, 31 October, 2018. Retrieved from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/210302018_Incheon_Communique_31_Oct._2018.pdf

WWF. (2016). Living Planet Report 2016. Gland, Switzerland. Retrieved from https://c402277.ssl.cf1.rackcdn.com/publications/964/files/original/lpr_living_planet_report_2016.pdf?1477582118&_ga=1.148678772.2122160181.1464121326